HOME PAGE

HOW

AMERICA'S GEOGRAPHY CREATED ITS IMMENSE POWER

by Dan

Moriarty, a high school economics teacher in

Massachusetts HOW

AMERICA'S GEOGRAPHY CREATED ITS IMMENSE POWER

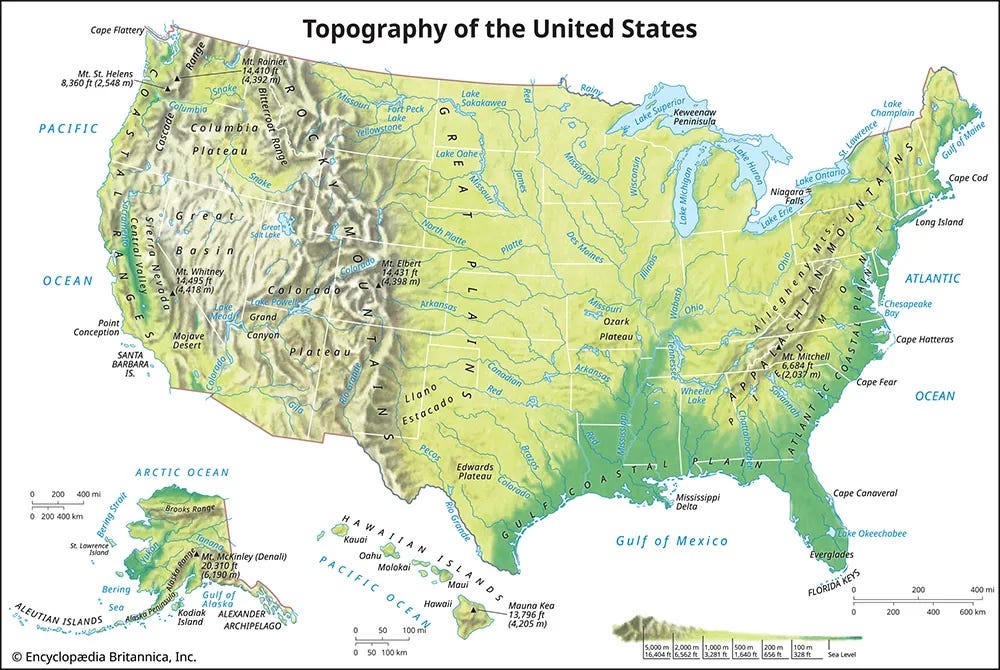

The unparalleled power of the United States is fundamentally a product of its unique geography, not just its policies or its ideology. While state power is a complex system, geography is the permanent, unavoidable stage on which it operates.

This physical reality—often overlooked—is the primary reason nations develop differently. The US is historically powerful not merely because it "plays the game" well, but because it was blessed with the world's most advantageous "playing field"; a combination of navigable rivers, natural ports, fertile land, and temperate climate that fostered organic economic growth and security.

THE PLAYING FIELD

The United States' geographic endowment is unparalleled, forming the foundation of its superpower status. Its most critical advantage is an immense and interconnected network of over 17,500 miles of navigable waterways, including the Mississippi River system and a sheltered coastline. This system, longer than the rest of the world's combined, provides incredibly cheap transport, turning inland cities like Pittsburgh into functional ocean ports. This hydrological blessing is compounded by an abundance of natural harbours, with more potential port capacity than could ever be utilised.

Furthermore, this transportation superhighway sits atop the world's most productive agricultural region, creating a perfect synergy for capital generation. This "tripod" of rivers, ports, and farmland resides largely in the temperate zone, ideal for economic activity and agriculture. Even its mountain ranges contain navigable passes, and the nation is rich in key natural resources like natural gas, timber, and oil.

Finally, America’s temporal luck was as important as its spatial luck; its westward expansion coincided with the Industrial Revolution. Technologies like railroads, refrigeration, and air conditioning allowed it to overcome arid regions, transforming potential liabilities into assets. Thus, while technology provided the tools for dominance, it was the unprecedented geographic bounty that generated the capital necessary to deploy them.

GEOGRAPHIC IMPACTS ON FORMATION OF THE STATE

Part 1: CAPITAL

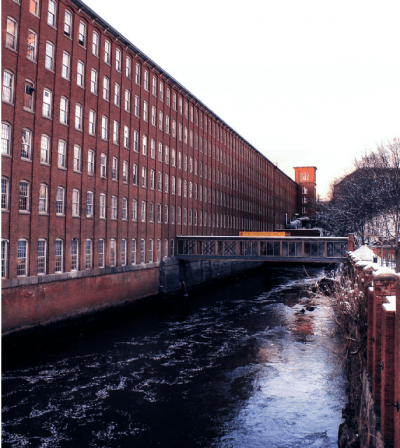

Applying Charles Tilly’s framework of natural capital and coercion, America’s geography made it uniquely suited for capital development. The U.S. has the most accessible and navigable internal waterways in the world, making it exponentially cheaper and easier to move goods domestically. Water transport, especially before the rise of railroads, was dozens of times cheaper than land transport. As a result, the U.S. developed robust internal trade, capital accumulation, and industrial specialization early on, particularly along its rivers.

Booth

Mill, Mass, water-powered in 1835

This natural abundance allowed much of America’s early development to occur without strong central planning. In the East and Midwest, entrepreneurs and settlers drove growth organically. By the time the Industrial Revolution arrived, the U.S. already had dozens of functioning urban centers near rivers, equipped with banks, schools, and infrastructure ready to scale.

The West was liberating in its vast open spaces and boundless horizon. In the American spirit, the West represents pioneers and self-determination, and the land west of the 98th Meridian would become the most potent force of abolition. While the region around Chicago became the industrial core that would later fuel the Union’s victory in the Civil War, the geography west of the 98th Meridian presented the opposite conditions—arid lands with few navigable rivers and little arable soil. The stark contrast of the 98th meridian is best shown by this image of U.S. light pollution. Here, the duality of American geography is clearly shown as population centers drop off a cliff traveling west.

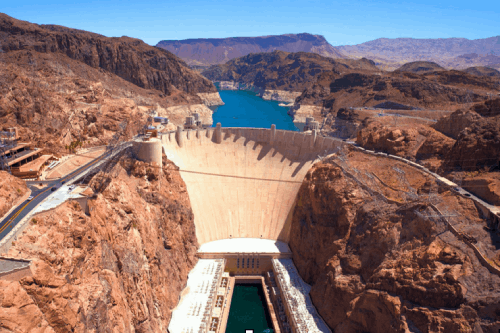

These conditions required significant state intervention to develop, including infrastructure projects and federal agencies like the Forest Service and Bureau of Mines.

This east-west divide gave rise to America’s hybrid identity: a decentralized, capitalist East and a state-managed, bureaucratic West. Railroads played a central role in unifying this vast country and were a major driver of the modern administrative state. Managing the massive rail system required new institutions like the Interstate Commerce Commission, which marked a shift in the relationship between the government, economy, and public.

Even as the state grew stronger in the West, America’s capital-rich nature shaped how that power operated. Projects like the Hoover Dam, though state-led, were built by paid, not coerced, labor, showing how capital still influenced even state endeavors. Geography also shaped America’s relationship with slavery. The South’s climate made it ideal for plantation agriculture and slave labor, while the North’s rocky soil and river power led to wage labor, industrialism, and stronger democratic institutions.

As the nation expanded westward, geography again undermined slavery: the arid West couldn’t support plantation crops, resulting in the rise of free states. The North’s industrial strength, built on coal, rivers, and capital networks, gave it the strategic advantage in the Civil War. The South, lacking comparable resources, centralized its government despite ideological commitments to states’ rights.

Post-war, federal efforts to develop the West opened it to capital investment, innovation, and entrepreneurship. Universities flourished across the country, many starting in small frontier towns. Unlike Europe’s concentrated elite institutions, America’s vast university system reflects its geographic sprawl and democratic accessibility. With nearly 4,000 institutions, the U.S. became a decentralized engine of knowledge and economic growth.

Ohio State University

In sum, America’s geographic advantages—its rivers, land, climate diversity, and isolation—shaped its economic development, limited its need for central planning (except where necessary), and helped form both its capitalist economy and modern bureaucratic state. These same geographic factors continue to underpin its global economic and military dominance.

GEOGRAPHIC IMPACTS ON FORMATION OF THE STATE

Part 2: COERCION

"States Make War and War Makes States, but Geography Makes Both."

The United States is a geographic fortress, shielded by vast oceans and benign neighbours. Its borders favour defence — rugged terrain along Mexico and deep economic integration with Canada make large-scale threats unlikely. This natural security enables the U.S. to project naval and air power globally without a heavy focus on homeland defence.

This isolation also fostered a self-reliant gun culture and a mindset of invulnerability. As historian Robert Kaplan notes, such security can encourage foreign policy overreach. The expansionist mentality born on the American frontier continues to shape U.S. global strategy.

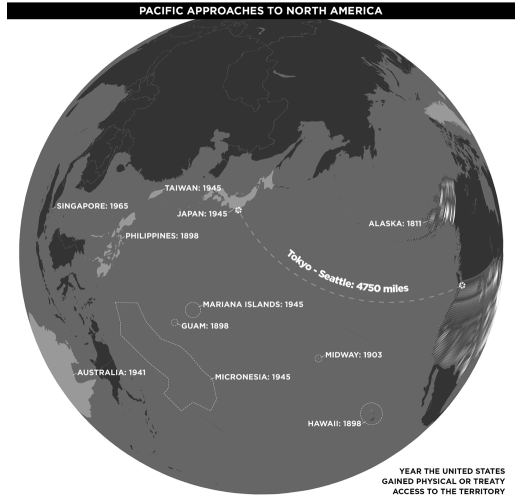

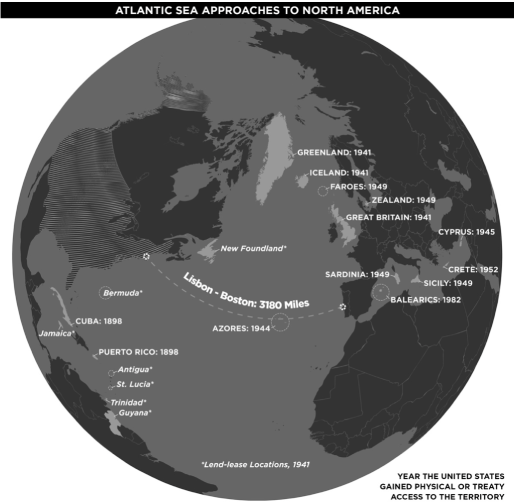

Historian Frederick Jackson Turner warned that the closing of the frontier threatened American identity, while Alfred Thayer Mahan emphasised naval dominance as the path to power. President Theodore Roosevelt merged these views, framing the oceans as America’s new frontier. This ideology, supported by geography, led to naval expansion and the Spanish-American War, gaining the U.S. overseas territories like the Philippines and Guam. However, unlike European empires, these were not vital for American survival, as the mainland was resource-rich and self-sufficient.

Post-WWII, the U.S. decolonized, aided by synthetic alternatives to tropical resources, and by technological advances that allowed global influence without occupation. Innovations in shipping and logistics enhanced its power projection, while the navy secured global trade, laying the foundation for globalisation through systems like Bretton Woods, NAFTA, and the World Trade Organisation.

Geography also shaped U.S. foreign policy duality: the resource-rich Eastern states encouraged bold moves, while the arid West bred caution. This was evident in George H. W. Bush’s aggressive approach to Iraq versus his restraint after Tiananmen Square and the Soviet collapse.

The American military base network reflects its frontier past — a “Frontier Imperialism” of strategic points rather than permanent occupations. Special forces play the role of modern frontiersmen, working with local factions much like in early U.S. territorial expansion.

Initial overseas holdings — desolate Pacific and Caribbean islands claimed for guano — became key bases during WWII. Many were already claimed, but the U.S. took them anyway, illustrating unilateralism rooted in frontier culture.

Geography destined the U.S. for global power, but its people remain shaped by localism. While elites are Wilsonian, the broader public leans Jeffersonian — products of the land that made the state and its many peoples.

THE IMPACT OF GEOGRAPHY ON AMERICAN POLITICAL AND CULTURAL IDENTITIES

America’s natural geography — vast, resource-rich, and defensible — has not only shaped its economy and foreign policy but also the diverse cultures and political identities of its people. From the rugged deserts of Texas to the icy hills of New Hampshire, Americans carved lives from difficult landscapes, forging a deep sense of ownership, independence, and practicality.

Life on the frontier demanded action, not theory. It was physical, dangerous, and survival-based — incompatible with abstract ideologies like Marxism or fascism. Communism’s rejection of private property clashed with the frontier ethos: you tilled the land, it was yours. American capitalism emerged not from intellectual salons but from pragmatic needs — math, barter, and trust — well-suited to frontier life. Even Enlightenment ideals were reshaped into self-evident truths rooted in lived experience.

The American state was built from the bottom up, with cultures rooted in geography. New England town halls reflect its community-focused, democratic legacy, while different regions evolved into distinct cultural “nations.” Historian Colin Woodard identifies eleven such nations. These regions remain politically and culturally divided today.

Geography allowed America to become a global hegemon, creating modern globalisation. But this global reach now clashes with the place-based identities of its people. Urban centres are becoming globalised “city-states.”

And so rural Americans, still tied to their land and traditions, feel alienated by modern liberalism, identity politics, and cultural homogenisation.

As cities grow cosmopolitan, many rural Americans feel their way of life is vanishing. Local cultures and economies are eroding under global consumerism, replaced by chain stores and unemployment. The fisherman now buys imported fish; the factory town becomes a ghost of itself. The result is not just economic decline, but cultural displacement.

This tension risks hardening into polarisation. A truly unifying leader today cannot be another Lincoln vanquishing one side, but someone who bridges the globalised and rooted halves of America. Global culture, unanchored from land and history, lacks something to fight for. In contrast, those tied to geography still defend a sense of place, tradition, and identity.

In an age of disconnection, geography remains America’s defining force — its strength, its fracture line, and its future.

SUMMARY

The United States became a superpower not through careful planning but by geographic default — the result of vast resources, ambition, and the relentless drive of pioneers, industrialists, rebels, and refugees. The American state was shaped by a chaotic, often violent expansion across a land so rich and immense that success became inevitable. This "destiny" wasn’t divine but geographic.

America’s vastness gave rise to a culture of independence, risk-taking, and global reach. Its size allows for military overreach that would bankrupt other nations, while its natural wealth supports unmatched multiculturalism. American identity, born from its geography, is not an ethnicity or religion but a mindset — fierce, diverse, restless, and shaped by the extremes of the land.

This land both divided and united its people. While it produced shameful histories like slavery and segregation, it also birthed abolitionism, civil rights, and feminism. American pluralism means its history includes both the persecutors and the resisters, the Klan and the Civil Rights Movement, prejudice and progress.

America's diversity is mirrored in its landscapes — from deserts to mountains, swamps to cities — and in its people, who trace their origins from every corner of the globe. They came as slaves, refugees, entrepreneurs, and adventurers. Some arrived millennia ago; others are here on student visas. Despite their differences, they’ve all been shaped by the same land.

American identity embraces contradiction — love and hate, liberty and oppression, ambition and humility. Its strength lies not in purity but in pluralism and resilience. To be American is to carry this complexity, to wrestle with a painful past while striving toward an inclusive future.

In the end, geography gave Americans the space to become who they are: not just citizens of a nation, but participants in an ongoing experiment. It is through this landscape, history, and shared struggle that Americans continue to define — and redefine — what it means to be American.